I personally really enjoyed the experience of the ‘Threads of Us’ workshop. It was my first time in 27 years being among exclusively POC queer people and getting the chance to connect with each other about the common cultural and racialised experiences of our queer lives. It was lovely to hear queer stories from younger people, feeling encouraged by the sense of community they had found. Coming together to create a united piece of work was especially beautiful and helped me feel like I was part of a community of queer POC I never had the chance to connect with before. I think the Tāmaki Makaurau workshop was powerful because it provided an opportunity for community connection in a space that was visibly ‘ethnic’ and queer as soon as I entered the space in the faces I saw, the activity at hand, décor that screamed ‘queer pride’, and the chai I was offered. The space felt comfortable to me in ways that exclusively queer and exclusively ‘South Asian’ spaces often do not. I felt encouraged and secure in my skin, my queer racialised experiences of life, and crucially, the political ideology by which I make sense of my world (i.e. there was a collective understanding of the oppressive, intersecting systems of racism, imperialism, colonialism, patriarchy, binary gender, transphobia, homophobia etc.). It felt like a space I could be ‘me’ in, without fear of judgement for my ‘otherness’ or perspectives.

From a theoretical perspective, I find it helpful to use Foucault’s concept of ‘pouvoir-savoir’ and the new conditions of possibility that become apparent when we create spaces that are alternative to hegemonic norms within a society. The space created a renewed sense of hope and joy within me as I realised the potential for new kinds of community that could form in ways that centre my ethnic and queer experiences as opposed to considering them “diversity tick boxes” or “add ons” to existing space. The experience really showed me that community has the power to come together and create the spaces we need -as evidenced by Adhikaar Aotearoa’s act of resisting traditional knowledge forms/putting money towards community connection first (instead of prioritising Eurocentric norms about ‘valid’ research outputs); Sahana’s story of finding her craft; and the stories shared by the ethnic queer university group about their fight for recognition. With regards to Foucault’s ‘Pouvoir-Savoir’, Spivak (1993) notes that in French: Savoir means ‘to know’ and Pouvoir means both the noun ‘power’ and the verb ‘to be able to’ - essentially articulating that we can only do things in so far as we can know/understand it as possible. It is only through the creation of spaces like the ‘Threads of Us’ workshop, that resist the Eurocentric, cis/heteronormative world around us, that living as a queer and racialised being becomes ‘knowable’ and therefore ‘doable’.

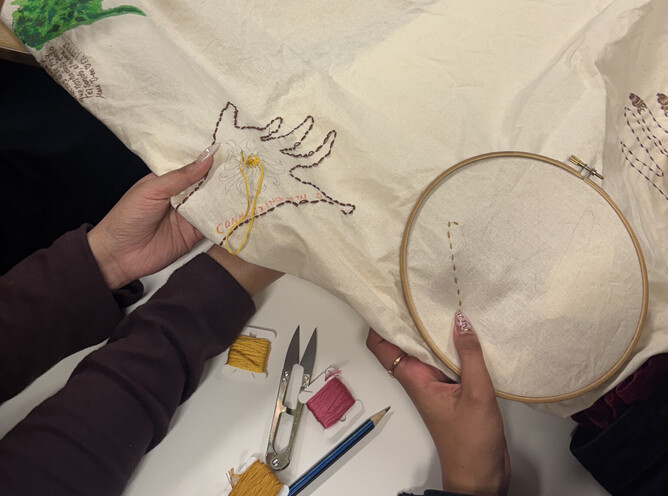

The activity itself also provided an opportunity to successfully embody the dialectic of honouring our individuality in close connection to/responsiveness to the collective community around us. Specifically, as we created our own individual piece on a broader piece of fabric, we had to exercise effective communication and patience with the people around us to work on our piece, without disrupting others too much/ enabling them to also complete their work. There was also beautiful symbolism in outlining our own individual hands and decorating them with personal embroidery style, whilst contributing to a single, collective artwork that would travel across the country – again showing us how our individuality can be part of and contribute to a whole without feeling diminished. This balance between individualism and collectivism, to me, represents the ideal kind of ethic that POC queer people can embody, between being true to ourselves while also understanding the importance of our connections and social relationships that confer obligations and ties onto us that realistically does restrict our movements to some degree (without automatically considering these connections pejorative, as Western individualism sometimes can). It felt like an honest reflection of the kind of ethics of liberation that I feel like is missing from some queer community spaces, which fail to consider the pragmatic aspects of community, while honouring heterogeneity and individual autonomy of community in ways ‘South Asian’ spaces often do not.

While I unfortunately could not stay to hear the discussion of ideas of thriving and suggestions for change, I’m confident that it was helpful for our communities to be given the space to discuss and share their ideas. According to Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) principles and some (limited) research on racial trauma, I would argue this activity has the potential to facilitate a degree of healing among the participants. For people who experience (multiple) kinds of marginalisation, we can feel very lonely and misunderstood. This space offered a chance to challenge that loneliness by connecting with others with similar experiences, and forming new bonds through the collective activity. Embroidery can also enable a sense of contact with the present moment and mindfulness (as per ACT principles) due to the careful, detailed, repetitive, and slow nature of the craft. This ‘embodied presence’ can facilitate healing among people with experiences of racial trauma, and likely other trauma related to discrimination and oppressive power. Reflecting on what thriving looks like and how to improve services can also be conceptualised as an opportunity for social action/activism, allowing participants to experience an opportunity for control over the narratives about them and to resist the dominant norms that shape the supports they have available to them.

In terms of improvement, I think there is always going to be a tricky balance to strike between trying to provide a non-white space without re-centring dominant groups within that alternative space. The space was (understandably) grounded in South Asian cultural ways of being (e.g. chai, south asian ethnicities were the majority, Bengali embroidery practice), which, while comforting to me, may be less resonant with other ethnic minority groups who were also present at the workshop (e.g. Pacific, Southeast Asian, East Asian community members). The group was also predominantly femme/WLW, and I wonder what more could be done to ensure ethnic minority queer people with more masc genders and gender expressions were aware of/felt able to attend (if anything)? I also have blinkers of privilege on when it comes to whether people of non-Indian ancestry, people with discriminatory experiences of colourism, casteism, and religious/cultural persecution on account of not being Hindu, felt as represented and comfortable in the space as I did. These things are important to consider given the intra-community tensions that continue to structure our experiences in diasporic communities. Critiques on ‘representativeness’ are also tricky to provide, as they speak to the issue of scarcity of ethnic minority queer spaces in general, as there ends up being more scrutiny and pressure on the singular spaces that ARE available to be responsive to ‘all’ needs – which is of course an impossible ask!

Suggestions for the future

Perhaps offering more guiding questions at the start to encourage connection, especially among quieter participants. This could be done through the form of written questions on the fabric itself or on cards near the food or something to encourage conversation.

Perhaps increased advertising on ‘mainstream’ queer organisations?

Perhaps more guidance around the kinds of services, events, and spaces participants can look to for future connection beyond this workshop?

Perhaps opening the space beyond university setting to capture broader experiences

Perhaps asking for permission to note down (e.g. on the fabric itself) some of the themes of discussion that come up during the workshops as there were some really interesting themes that came up (e.g. concern about the future/jobs/economy, increasingly violent transphobic rhetoric, the ways in which future generations are at times experiencing more progressive parenting approaches etc.)