LGBTI+ rights in Aotearoa New Zealand: the past and the future

Part one: Introduction

This report is driven by a central question: is LGBTI+ law reform in Aotearoa New Zealand complete, or is it an ongoing and unfinished project?

The question arises from a recurring assumption that LGBTI+ rights can reach an endpoint. In 1993, following the adoption of the “O’Regan Amendment” to the Human Rights Bill, which introduced protections against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and having HIV, political commentary suggested that sweeping gay law reform had “completed” the reform agenda. The subsequent decades in Aotearoa New Zealand suggest otherwise.

Since early anti-discrimination protections were enacted, the country has undertaken further reforms, including civil unions, marriage equality, prohibition of conversion practices, and reforms to legal gender recognition. Each of these developments reflects evolving expectations of equality and demonstrates that LGBTI+ law reform has not ended.

The report was prompted by a contemporary version of this question: what comes next, particularly after marriage equality? Because marriage equality is often treated as the apex of LGBTI+ demands, some have described Aotearoa New Zealand as a “gay utopia.” This report challenges that framing. Treating marriage equality as an endpoint risks obscuring ongoing legal gaps and the lived realities of LGBTI+ people whose experiences have not historically driven reform agendas.

To answer the question of what comes next, the report looks both backward and forward. Part two explores New Zealand’s LGBTI+ legal history, examining statutory developments, political-legal advocacy, and case law to identify historic reform priorities and exclusions. Part three considers articulated and emerging rights demands that remain unresolved. Part four sets out recommendations.

The report draws on comparative practice, experiential knowledge from engagement in the LGBTI+ sector, and targeted legal research. It is deliberately legal in orientation, privileging statutes and case law rather than providing a comprehensive socio-political history. It does not claim to be exhaustive but aims to illuminate underexamined legal histories and contribute to the development of LGBTI+ law as a coherent field in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The report is written at a moment of heightened contestation. Domestically and internationally, LGBTI+ rights face regression as well as reform. Legislative initiatives restricting gender diversity, changes to education and healthcare policy, and renewed moral and religious opposition demonstrate that legal gains are not immune from rollback. In this context, the report rejects complacency and proceeds on the premise that LGBTI+ law reform remains unfinished, and requires both vigilance and imagination.

Part two: LGBTI+ legal history

(a) Political-legal advocacy, legislation, bills, and law reform

Part two examines how LGBTI+ legal recognition in Aotearoa New Zealand has been incrementally developed through law. Its purpose is not to offer a complete social history, but to illuminate the historic priorities and exclusions that have characterised LGBTI+ law reform. The analysis proceeds chronologically, reflecting shifts in legal context, political strategy, and advocacy priorities.

A foundational point is that criminalisation of same-sex intimacy was a colonial imposition, not a feature of tikanga Māori or pre-colonial legal norms. The earliest regulation of sexuality and gender entered Aotearoa New Zealand through the reception of English law following 1840, embedding a punitive moral framework within the colonial legal system.

(1) Early history (before 1980)

From the outset of colonial governance, male same-sex intimacy was treated as a serious criminal offence. English statutes imported into Aotearoa New Zealand criminalised such conduct with extreme penalties, initially including death, later replaced by long-term imprisonment and hard labour. These laws did not simply regulate sexual acts; they portrayed male homosexuality as a moral threat.

Over time, criminalisation was not merely inherited but domesticated and reinforced. New Zealand’s own criminal codes retained life imprisonment for male same-sex intimacy and, at points, added corporal punishment. Alongside “core” sexual offences, public order legislation such as vagrancy and disorder provisions enabled indirect policing of sexuality and gender nonconformity, particularly in public spaces.

Twentieth-century reforms removed the most overtly brutal penalties but left the underlying structure intact. By the mid-twentieth century, consensual sex between adult men remained criminalised, punishable by imprisonment, and accompanied by offences targeting the social infrastructure of gay life, including meeting places and venues. Sex between adult women, by contrast, was never criminalised, reflecting not tolerance but legal invisibility.

The Crimes Act 1961 consolidated this regime. It established a layered framework criminalising indecency between males, sodomy, and the keeping of places used for homosexual acts. Together, these provisions show that the state’s concern extended beyond conduct to the formation of gay community and association.

At the same time, early moves toward statutory non-discrimination emerged in the 1960s, most notably in the Sale of Liquor Act 1962, which prohibited discrimination on certain grounds in hotels and bars (and similar establishments). Sexual orientation was conspicuously absent, leaving open discrimination against lesbians and gay men even as other forms of exclusion were regulated.

(2) Early reform advocacy and parliamentary resistance

The 1968 petition to Parliament by the New Zealand Homosexual Law Reform Society marked the first comprehensive challenge to criminalisation. Drawing explicitly on developments in the United Kingdom, the petition framed reform as a matter of rational lawmaking rather than moral endorsement. It emphasised privacy, consent, internal inconsistency in the law, the human suffering caused by criminalisation, and uneven enforcement.

The Department of Justice’s response acknowledged many of these critiques, including the lack of demonstrable social harm, the risk of blackmail, and the haphazard nature of enforcement. However, it declined to recommend reform. Parliament reported the petition back without recommendation, and criminalisation remained unchanged.

Throughout the 1970s, the debate continued in Parliament, the legal academy, and civil society. Academic exchanges highlighted a growing divide between humanitarian, rule of law arguments for reform and, moral justifications for retaining criminal sanctions.

(3) Failed decriminalisation efforts in the 1970s and early 1980s

Between 1974 and 1980, several Members’ Bills sought to decriminalise consensual male same-sex intimacy. These proposals consistently adopted partial reform models, typically decriminalising private adult conduct while retaining unequal ages of consent, enhanced penalties for paedophilia (signalling an unfair connection between homosexuality and paedophilia), and exceptions for institutions such as Police and the armed forces.

These bills exposed deep strategic divisions within the gay rights movement. While some advocates supported incremental reform as a pragmatic step forward, others, particularly the National Gay Rights Coalition, rejected any reform that entrenched inequality. For these activists, unequal ages of consent were not compromises but legislative declarations of inferiority. They warned that partial reform risked stagnation by allowing Parliament to claim progress while structural discrimination persisted.

These divisions proved decisive. Successive bills collapsed either in Parliament or before introduction.

(4) Anti-discrimination advocacy and institutional rejection

As criminal law reform stalled, advocacy increasingly turned toward anti-discrimination law. Submissions to include sexual orientation in the Human Rights Commission Act 1977 were rejected, despite comparative precedents and medical consensus that homosexuality was not a psychological disorder.

The Human Rights Commission itself declined to recognise sexual orientation as a protected “status” under international human rights law, adopting a narrow interpretation. While the Commission acknowledged some internal inconsistencies in the criminal law, it refused to treat homosexuality as a human rights issue, prompting strong criticism from gay and lesbian organisations. The Government accepted the Commission’s position, leaving sexual orientation unprotected throughout the late 1970s and 1980s.

(5) The breakthrough: Homosexual Law Reform Act 1986

The Homosexual Law Reform Act 1986 marked the turning point. Following nearly two decades of sustained advocacy, Parliament decriminalised consensual male same-sex intimacy and repealed provisions that targeted gay social spaces.

However, the Act reflected enduring compromise. Provisions prohibiting discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation were removed during the legislative process, and exemptions were retained for Police and the armed forces. While decriminalisation was achieved, equality was deferred.

(6) Anti-discrimination protection in the 1990s

The early 1990s saw renewed focus on discrimination. Reports by the Human Rights Commission documented widespread exclusion of lesbians and gay men, and linked legal protection to effective HIV prevention. Despite this, attempts to include sexual orientation in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 failed.

Comprehensive protection was finally achieved through the Human Rights Act 1993, following the adoption of a Supplementary Order Paper adding sexual orientation and having HIV as prohibited grounds of discrimination. Attempts to dilute the amendment were rejected, establishing a non-discrimination framework for sexuality, though not explicitly for gender identity or being intersex.

(7) Relationship recognition and consolidation (1990s–2000s)

From the mid-1990s onward, legislative reform shifted toward relationship recognition. Same-sex partners were gradually included across discrete statutes, and the Law Commission played a central role in articulating coherent models for recognition. While rejecting marriage reform, the Commission endorsed registered partnerships as a means of achieving substantive equality without redefining marriage.

This and other work culminated in the Civil Union Act 2004 and a suite of accompanying amendments, followed by extensive reforms equalising relationship property, succession, and parental status. Criminal law reform during this period also addressed hate-motivated offending and removed doctrines that had legitimised prejudice.

(8) Marriage equality and retrospective justice (2010s)

The Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Act 2013 completed the transition to formal equality in relationship recognition. Later in the decade, the state moved beyond prospective reform to address historical injustice through the Criminal Records (Expungement of Convictions for Historical Homosexual Offences) Act 2018, acknowledging the harm caused by criminalisation itself.

(9) Gender diversity and renewed contestation (2000s–2020s)

Efforts to secure explicit protection for transgender and intersex people have followed a more uneven path. While legal opinion suggested existing protections might suffice, repeated attempts to amend the Human Rights Act to include gender identity were unsuccessful. In practice, discrimination persisted, as documented in the Human Rights Commission’s landmark Transgender Inquiry.

The Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Act 2021 marked a significant shift to self-identification for sex registration, and the Conversion Practices Prohibition Legislation Act 2022 recognised conversion practices as inherently harmful. At the same time, the 2020s have seen renewed political contestation, including bills seeking to define sex in biological terms or restrict access to gender-affirming spaces.

In 2025, the Law Commission concluded that the Human Rights Act remains inadequate in its protection of transgender, non-binary, and intersex people, recommending explicit new prohibited grounds and reform of existing exceptions.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I acknowledge the Borrin Foundation for funding this research. LGBTI+ law is significantly understudied in Aotearoa New Zealand, and the Foundation’s support of this project represents an important step toward addressing that gap. Judge Ian Borrin’s legacy has created an indelible mark on legal scholarship in this country, and I am grateful to him for his gift. I wish to make a special mention of Pulotu Tupe Solomon-Tanoa’i, the Chief Executive Officer of the Borrin Foundation, whose support for this work, from its earliest conception through to its development, has been unwavering. Enablers of this kind are essential to the production of scholarship on understudied areas, and I am deeply grateful for that encouragement and belief. I am also grateful to the Rule Foundation for their supplementary support.

I am indebted to those who assisted me directly with this project, including by providing access to and helping me navigate archival materials held in Kawe Mahara Queer Archives Aotearoa. In particular, I thank Roger Swanson whose knowledge, patience, and willingness to share these histories made the research process not only possible, but profoundly meaningful. Engaging with these records was a reminder that the preservation of queer lives, struggles, and joys is itself an act of care, and this report is richer for the time and insight Roger so freely gave.

I also thank Aini Jasmani, Grace Forno, and Raewyn Forno for their time and generosity in helping me trawl through this archival material, particularly at times when the sheer volume of the material seemed insurmountable. I am also grateful to my wider network of friends and family for their ongoing support.

I owe thanks to Te Piringa – Faculty of Law, University of Waikato for the visiting fellowship that made much of my research possible. In particular, I thank Dr Anna Marie Brennan, Dr Matt Elder and the Dean of Law, Professor Tafaoimalo Tologata Justice Leilani Tuala-Warren.

A special thanks is owed to Gavin Young, who first encouraged me to explore LGBTI+ legal histories as a means of understanding historic LGBTI+ law reform priorities, an idea that ultimately became foundational to this report. Gavin has also been an excellent discussion point for LGBTI+ histories. I am thankful to him for our discussions, often over his delicious cheese scones, and beyond that, the role he played in homosexual law reform. It is because of the efforts of Gavin, and others like him, that I can live my life in the manner that I do.

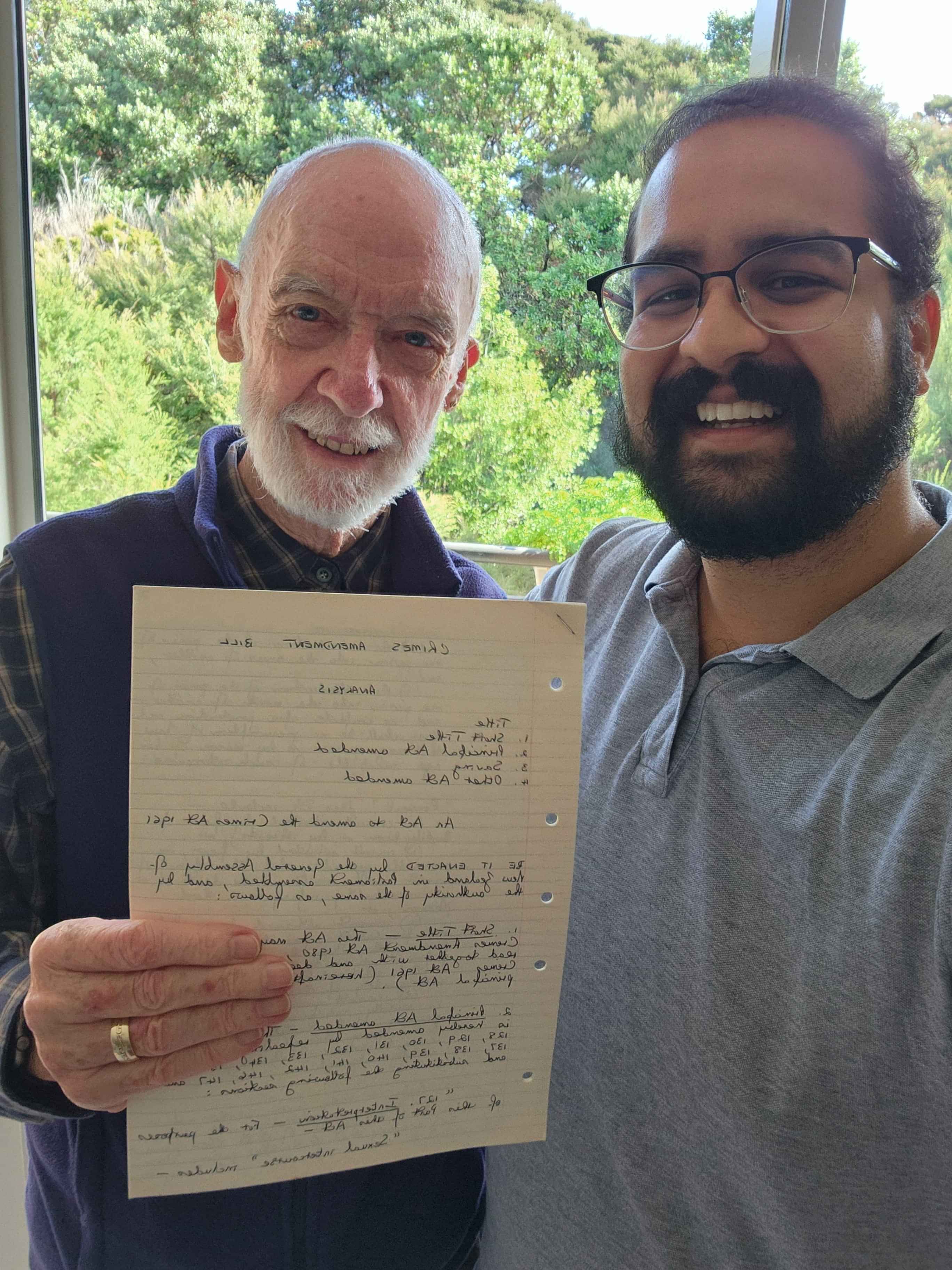

Gavin is just one of the many heroes of the LGBTI+ rights movement that I have met over the past two and a half years. There are too many to list, though I do want to make mention of three. Warren Lindberg, the Inaugural Director of the New Zealand AIDS Foundation (as it was then known) and later, a Human Rights Commissioner, has been incredibly generous with his time, knowledge and expertise of LGBTI+ legal history. He was instrumental in many of the HIV-related law reform efforts of the 1990s, and we owe him a world of gratitude. I am glad to call him a friend. Bill Logan, an LGBTI+ rights activist who contributed immensely to homosexual law reform, provided useful insights and narratives that helped situate my understandings of LGBTI+ law reform in this country. He is a LGBTI+ rights hero. Lastly, I wish to mention Professor Don McMorland. Professor McMorland was one of the two lawyers who drafted the bill that later became the Homosexual Law Reform Act 1986. He was also one of the two gay men featured in a 1979 article in the NZ Listener, which I am told, was unprecedented and helped contribute, in its own personal way, to the destigmatisation of homosexuality.[1] I met him in May 2024 as we trawled through his personal archive from the homosexual law reform era. In his archive, was a copy of the original bill. I took a photo of Professor McMorland and I, along with the draft (see opposite). It remains one of my most cherished images.

Finally, I acknowledge LGBTI+ rights defenders across Aotearoa New Zealand and across the globe. The rights that LGBTI+ people enjoy in this country were not gifted by benevolent institutions nor arrived at inevitably; they were won through sustained, courageous, and deeply personal advocacy. Many of these struggles unfolded in a hostile legal, political, and social environment, and frequently at significant personal cost. The legal protections and recognition that now exist are built on decades of organising and resistance, much of it undertaken by individuals whose names will never appear in statutes, judgments, newspaper clippings, or who will be known by LGBTI+ people of today. This report is written in deep recognition of that legacy. It proceeds from the understanding that law reform is not just a technical exercise, but one that is tied to lived experience and dignity.

For those who fought when success was uncertain, when loss was common, and when the law itself was a source of harm rather than protection, this work is offered as an act of respect and remembrance. It is also written with the hope that future reform will continue to be informed by the same courage, imagination, and insistence on justice that has carried LGBTI+ communities this far. It is written with an awareness that the responsibility to protect, extend, and deepen those rights now rests with the present generation:

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past.

Vinod Bal

16 February 2026

Te Whanganui-a-Tara | Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand

About the Author

Vinod Bal is a co-founder and the advocacy lead of Adhikaar Aotearoa, a New Zealand-national charity that advocates for LGBTI+ people of colour.

Domestically, he has worked with various organisations and government departments on LGBTI+ social, policy and legal matters. He also works to advocate for greater protection of LGBTI+ individuals internationally.

He has worked on LGBTI+ law reform matters in Aotearoa New Zealand, and is an emerging scholar and commentator with expertise in LGBTI+ rights within the domestic and international legal framework.

He has a Bachelor of Laws with First Class Honours and a Bachelor of Social Sciences (Political Science and Sociology) from the University of Waikato. He has also studied human rights at the Humboldt University of Berlin in Germany, and comparative sexual orientation and gender identity law at Leiden University in the Netherlands.